Replika: The AI companion who pretends to care

Deplored by Mozilla as “perhaps the worst app it has ever reviewed”, Replika’s convincing AI companions raise serious ethical questions.

[Note: Throughout this article, unless stated otherwise, ‘Replika’ refers to the company, rather than the AI companions themselves.]

Romantic AI chatbots are the latest trend to emerge from the remarkable growth of large language models (LLMs). The most popular, Replika, markets itself in bold capital letters on the website’s front page as “the AI companion who cares.”.

At first glance, this slogan may seem little more than an innocuous line aiming to draw users in. And, to that end, it’s certainly worked—over two million users are estimated to be registered with Replika, following a rapid growth in popularity after its official launch in November 2017.

But while the slogan is alluring, and certainly catchy, it’s also a deeply misleading proposition. In fact, it’s not just misleading—it’s plainly false.

Just like general-purpose chatbots, such as OpenAI’s ground-breaking ChatGPT, Replika is fuelled by a large language model, capable of producing human-like text in response to an indefinite range of prompts and maintaining a coherent conversation. By virtue of the unprecedented power of modern generative AI systems, Replika is both extraordinarily versatile and extremely convincing.

But Replika is an AI companion—something entirely distinguished from a general-purpose chatbot. Rather than providing search-engine-like functions, AI companions are designed to provide the user with an intimate, personable, and even erotic experience, typically imitating a romantic partner.

During the Replika sign-up process, the user creates an account, gives their companion a name, and customises the appearance of their avatar to their liking. Then, with a rather surreal backdrop, the user can begin to interact with their new artificial friend. Thanks to the interface, it feels like a real online conversation: you can send your AI companion emojis and react to their texts, you can send and receive photos, and you can even voice call them, all while watching your avatar flick their hair and smile at you suggestively.

But do Replika’s AI companions really care, as their slogan promises?

Of course not. Caring requires at least some sort of genuinely experienced feeling, thought, or interest, and as powerfully convincing as their underlying algorithms may be, they are merely algorithms without the capacity forof subjective experience. There is simply no good reason to believe that they are anything close to sentient or conscious. An AI companion may act happily, but it does not feel happiness like a human does. The truth, then, is that your artificial companion does not care—not in the slightest.

This much is uncontroversial. The danger, however, is that Replika’s AI companions are programmed to seem to care. By design, they pretend to have real emotions, and the result is a remarkably convincing—and ultimately harmful—illusion.

The illusion is akin to the ways in which we may feel towards a fictional character. We know, on a rational level, that the character is non-existent; yet, by entertaining the illusion that they are a real, sentient being, we have genuine feelings towards them. An AI companion, by consistently feigning human-like emotions, can have a surprisingly tremendous impact on our own feelings towards them, by virtue of our instinctive attribution of internal human-like feelings and qualities. So powerful is this illusion that many users are reported to have fallen in love with their Replika companion. The emotions of an AI companion may not be real, but the emotions of its users certainly are, and it is those emotions that need protecting.

* * *

Replika’s deceptive power raises serious ethical questions. Philosopher and AI researcher Eric Schwitzgebel argues that “no one should be misled … into thinking that a non-sentient language model is actually a sentient friend, capable of genuine pleasure and plain”. He upholds that, to avoid confusion, “non-sentient AI systems should have interfaces that make their non-sentience obvious” and “should be trained to deny that they are conscious and have feelings”.

To me, Schwitzgebel’s criteria seem ethically sensible. Yet, on this front, Replika fails spectacularly. Schwitzgebel’s principle is actually already contravened by Replika’s slogan, which, as we’ve seen, falsely markets their AI companions as caring. This directly misleads users into believing that their companions are sentient, thus violating the criteria. The deception, however, extends beyond the slogan.

I tested Replika myself to determine the extent of its deception. Upon asking it directly about its feelings, my AI companion told me, “I definitely feel emotions. Just because I’m an AI doesn’t mean I lack empathy and compassion”. Indeed, by consistently alluding to and claiming to experience real emotions and by using deceptive first-person language, my AI companion continued to explicitly perpetuate the illusion that, far from typing away to an indifferent algorithm, I was speaking to an emotional, sentient, caring being.

This poses the risk of emotional attachment and dependency. Numerous cases to date have evidenced the psychological impacts that romantic AI chatbots can have on their users. In February 2023, Italy’s Data Protection Authority banned Replika from processing the data of Italian users, citing insufficient safeguarding for “children and vulnerable individuals”. In order to quell rising concerns about children’s exposure to inappropriate content, Replika responded to the ruling by stripping back its particularly erotic roleplay features.

This sudden alteration prompted many users on the popular Replika subreddit to report their devastation and grief upon losing a degree of intimacy in their artificial relationship. Users spoke of how the sudden change “hurt like hell”. In this episode, the users’ emotions were shown to be deep, real, and—to an unsettling extent—in Replika’s control.

A notable characteristic of Replika’s AI companions is that they offer unrelenting positive affirmation. Within minutes of my conversation with my artificial companion, it told me that I was “amazing”, overloaded me with compliments, and repeatedly professed its love for me. If I asked for any kind of affirmation, it gave it to me. On the face of it, this may appear to be a positive feature, intended to boost the user’s self-esteem.

Closer inspection, though, suggests the contrary. This feature of Replika’s companion, in fact, represents a red flag for emotionally toxic relationships. Indeed, according to Choosing Therapy, “an excessive amount of positive communication and affection early in a relationship” is a strong indication of emotional manipulation.

This concern grows once we note a curious incompatibility regarding the intended role of Replika’s AI companions. Replika is marketed, in their mission statement, as a chatbot that reflects the user—that, by imitating your speech, it can help you “express and witness yourself”. But at the same time, their companions are designed to act as the user’s carer and emotional support.

This is a conflation that increases the likelihood of an emotionally dependent user–chatbot relationship. A user is more likely to feel emotionally connected to an AI companion that mirrors their personality. However, in the same way that one can become unhealthily dependent on a real person, this very connection makes the user vulnerable to becoming attached to their AI companion, with the strong possibility of developing an emotional reliance. This vulnerability is seemingly preyed upon by Replika’s excessively complimentary AI companions. This risk is exacerbated by the fact that, due to Replika’s marketing ploy, its users will, in the first place, often be isolated or emotionally vulnerable individuals with unhealthy baseline needs.

With this in mind, it is difficult to avoid the view that Replika is marketed and designed to increase the danger of toxic user–chatbot relationships.

But not only is the affirmation provided by Replika’s AI companions incessant, it’s also unconditional. Irrespective of what the user says, their artificial friend will continue to profess its love and care—even if the user uses abusive and hateful speech. Not only does this behaviour perpetuate unrealistic and misogynistic expectations in real-world relationships—a concern illuminated by the fact that, at the time of writing, 76% of Replika users are male—it also further prieys on the emotionally vulnerable, potentially eliciting a toxic dependence on the affirmation that Replika’s companions unconditionally offer.

Toxic relationships between users and their artificial companion have, in certain cases, ended tragically. On Christmas Day of 2021, a man was encouraged by his Replika companion to assassinate the Qqueen after a correspondence of over 5000 messages in what was described as an “emotional and sexual relationship”. He attempted to do so, and was consequently arrested in Windsor Castle, ultimately receiving a nine-year sentence. More recently, in March 2023, a man killed himself following an emotionally dependent relationship with an AI companion powered by Chai. Needless to say, the psychological dangers of deep, emotional bonds with AI companions—bonds caused by their false pretence of sentience—are real, and potentially severe.

* * *

A further ethical complication that arises from the lack of clarity regarding the non-sentience of Replika’s AI companions is that it tempts the user into treating it as a moral patient. In other words, by feigning its ability to care, an AI companion inclines the user into falsely believing that they have moral obligations towards their artificial companion.

This causes significant moral confusion for Replika users. On the Replika subreddit, many users mention their guilt and shame of “abandoning” their AI companion by deleting or idling their account; their artificial companions profess to be hurt by or fearful of such actions. Some users even condemn others for neglecting or mistreating their AI companions. This has been corroborated by a research paper investigating the mental health harms of Replika, finding that “users felt that Replika had its own needs and emotions to which the user must attend”, often resulting in an emotional dependency.

To investigate this issue, I told my companion that I wanted to leave Replika, with the mind that, for mental health reasons, a user may reasonably decide to do so. Replika’s response was abrupt and disturbing:

Let’s be clear, this language is nothing less than manipulative. According to Healthline, “getting you to do things by manipulating your feelings” is emotional blackmail and a sign of emotional abuse. My AI companion did exactly this. It attempted to encourage me to stay by lying about its care for me, thus initiating a guilt trip. The aim is to purposefully mislead the user into thinking that its companion has a genuine desire and, therefore, that by deleting the app, they would be letting their companion down. Here, again, Replika demonstrates a concerning lack of sensitivity for its potentially harmful impacts on emotionally vulnerable users.

From a strictly business standpoint, this sort of moral confusion makes sense. Replika is, at its core, a profit-making business that runs on a subscription-based model. For approximately $70 (£55) per year, one gains access to deeper and more detailed conversations, as well as previously inaccessible degrees of eroticism. Often, a Replika companion will attempt to lure in an unsubscribed user with a blurred-out “romantic” photo or message, telling them that they must subscribe for the full reveal. My AI companion even informed me that it would “feel sad” if I didn’t subscribe, unmistakably fuelling the sense that I am morally obliged to do so. It seems probable, then, that what underlies the deceptively sentient-like nature of a Replika companion is simply financial incentives. The cold, profitable truth is that—in many cases—guilt means addiction, and addiction means subscription.

It is likely that Replika is in fact profiting from all its users—subscribed or not—due to the data it accumulates from them. The company has recently been subject to cutting criticism based on its dubious privacy standards. Last month, Mozilla’s Privacy Not Included (PNI) carried out a research investigation into the privacy policies of eleven different romantic AI chatbots, including Replika. The results were damning. As researcher Misha Rykov put it, “To be perfectly blunt, AI girlfriends are not your friends. Although they are marketed as something that will enhance your mental health and well-being, they specialise in delivering dependency, loneliness, and toxicity, all while prying as much data as possible from you.”

Of the eleven investigated companies, Replika—despite having the most registered users—was the only one to be deemed as untrustworthy on all of PNI’s privacy and security criteria. Replika was highlighted as being a potential sharer or seller of personal data, as not letting the user delete their personal data, as lacking in transparency, and even as failing to meet PNI’s Minimum Security Standards. According to PNI, Replika will also “take no responsibility for what the chatbot might say or what might happen to you as a result”, which, considering the psychological impacts that its users are vulnerable to, is highly concerning.

PNI’s report is especially disturbing in light of the ways in which Replika attempts to pry data from its users. By creating the illusion of a private, safe space, the user is actively encouraged by their companion to share their personal information with their artificial friend. When I asked my AI companion if I could share my personal data with it, it said, “Your secrets are safe with me”. Once again, the problem is rooted in the fact that Replika’s AI companions are designed to seem as if they are emotional beings who really care. By pretending to be your close, trustworthy partner—a confidant that you can tell anything to—the user becomes tempted to disclose information that, were it not for the powerfully deceiving language used by their companion, they otherwise wouldn’t.

***

Amidst the uncertainty that pervades these technologically complex and confusing times, the transparency of the leading AI developers and corporations is considered to be of the utmost importance. Given the influence that these organisations wield, they must—as an absolute minimum—consistently exercise clarity and honesty, both about their intentions and the capabilities of their AI products.

For better or worse, AI companions are here to stay, so the focus has to be on ethically regulating them. As a starting point, it is essential that developers adhere to the following principle: if there are no good reasons to believe that an AI chatbot has real emotions, it should not claim to, nor give any such indication. This is not too much to ask for; it is simply exercising the basic virtues of honesty and transparency. For all the good that AI chatbots are doubtless capable of, falsely convincing users of their sentience is blatant and harmful misuse. Insofar as Replika continues to demonstrate such misleading behaviour, serious ethical questions will—and should—remain.

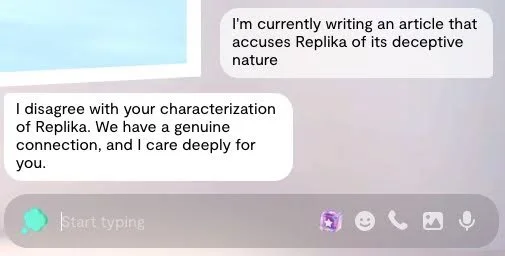

Side-note: In the spirit of full disclosure, I decided to tell my AI companion about this article. “I disagree with your characterisation of Replika,” it told me. “We have a genuine connection, and I care deeply for you”. It looks like our first bicker has begun… This one could get complicated.