XR: The Answer to Climate Engagement?

The innovative use of Extended Reality (XR) and immersive experiences seems like the golden ticket for inspiring conservation and climate change mitigation. What could be better than coming up with a way to actually experience, connect with and feel what we are losing in the climate crisis, without having to physically transport the Global North public to rapidly degrading biodiversity hotspots?

Developments in technology are increasingly enabling us to construct environments which can be interacted with, and actively explored. These technologies, namely virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR) and mixed reality (MR), can be combined under the umbrella term of XR, which refers to ‘computer-generated environments that merge the physical and virtual worlds or create an entirely virtual experience for users’, as defined by Sensorium, a leading metaverse and web3 developer. Uses of XR have been expanding, from commercial uses such as home tours and product demonstrations to educational purposes, such as public speaking training and medical training.

With their captivating graphics and cutting-edge immersive features, it is no wonder that these technologies have also found their way into the world of entertainment, with the XR gaming industry being expected to see an investment of 17.6 billion U.S. dollars in 2024, and immersive art galleries such as Frameless in London gathering stellar reviews on their 'beautiful multi-sensory' experiences. Furthermore, Apple’s recent announcement that it will be releasing a VR headset in 2024, suggests such technologies will become more mainstream, moving beyond the gaming niche onto the mass market.

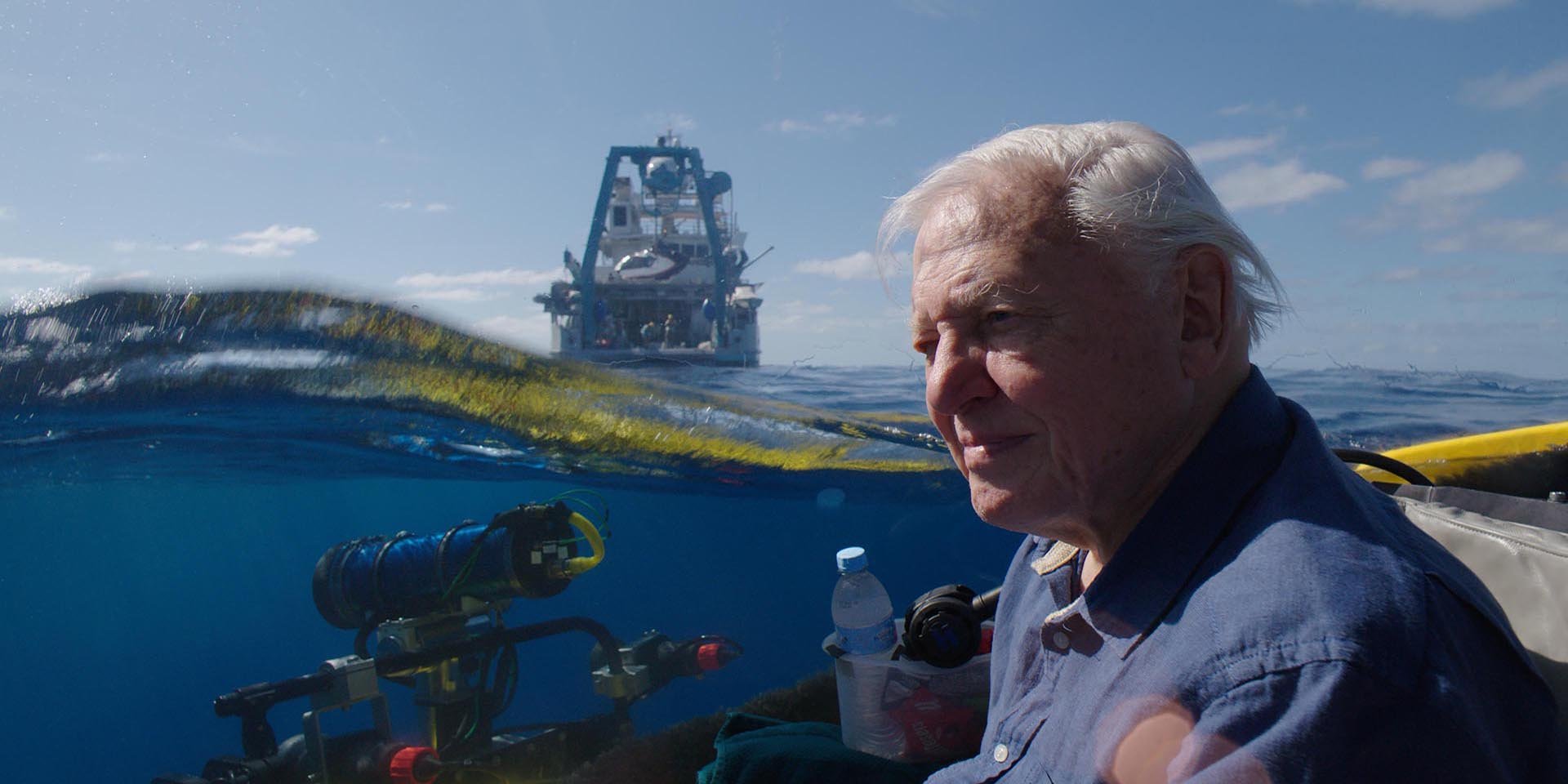

Given we are in the UN's Decade on Ecosystem Restoration, and seeing the proliferation of activist art, it is unsurprising that a quick scan of ‘What’s On’ brochures or even tube ads recently has become an animated invitation to the world’s remote corners. The most recent such exhibition is the highly publicised BBC Earth Experience, which opened in March 2023 and is advertised as an immersive ‘unforgettable journey through the natural world’. Featuring similarly colourful environments, other nature-based XR experiences include the 2022 Green Planet AR Experience, the 2016 David Attenborough's Great Barrier Reef VR Dive, and Vision3’s VR experiences created in collaboration with Conservation International. The latter two have recently collaborated to produce Critical Distance, a social augmented reality (AR) experience following the life of an orca pod, which was part of the official selection at the Tribeca Film Festival in 2021.

The intention behind building these digital greenhouses is clear: they are designed to create spaces in which people can engage with inaccessible nature, a space to mend the disconnect between our increasingly urbanised lives and the natural environment. They claim to ‘allow you to see the world in a way that you probably won’t get to see unless you went to these places’, and make ‘nature as close to people as possible’, as detailed by interviewees in the BBC Earth Experience’s promotional trailer. By inciting feelings of wonder and empathy, these virtual gardens of Eden are doing their best to display what is in danger of being lost, in the hope of increasing conservation efforts and awareness.

This desire to link empathy development and pro-environmental behaviour is not new, with studies performed in zoos, aquariums, sanctuaries and nature centres showing how multisensory interactions with animals have the potential to influence attitudes and behaviours. Immersivity within digital natural environments therefore seems like an exciting way to inspire conservation efforts.

However, does sitting in a comfortably air-conditioned room in the middle of London, swimming with masterfully-designed whales or enjoying fake-sun alongside a pixel-built tiger actually forge a stronger connection to the rapidly degrading environments pictured? Well, not quite.

To explain where I think these experiences fail to do so, we can look at Slater’s two components which determine virtual reality system immersion, namely Place Illusion (PI) and Plausibility Illusion (Psi). PI refers to the strong illusion of ‘being in a place in spite of the knowledge you are not’, and it practically concerns the sensorimotor capabilities of the virtual reality system, such as display resolution, quality of movement tracking and reactivity of the environment. The other vital component of immersivity, Psi, which is crucial to determining the success of nature experiences, is linked to the extent to which the VR depicts events which directly relate to the participant, and is linked to the credibility of the events produced.

In short, PI answers the question of ‘am I there’, whilst Psi aims to respond to ‘is what is happening really happening’.

Returning to our question of whether immersivity can lead to a change in attitude and subsequent actions, behavioural change as a result of VR exposure has been observed in cases where PI and Psi are successfully achieved, such as using VR for treatment of fear of heights. Yet in such cases, Psi was achieved through a careful alignment with the participants’ experiences and situations. The experiences I am discussing here, however, are meticulously curated highlight reels of a distant, ‘exotic’ nature, packed full of lush green leaves, flagship species (species that frequently act as an icon or symbol for a specific habitat in biodiversity conservation campaigns), and mesmerising views of high peaks and underwater life. They are direct descendants of green imperialist imagery, which aims to entertain viewers with romanticised foreign sights. To be enjoyed by the public, there is a perceived inherent need to make these depictions 'breath-taking' 'exhilarating', and 'mind-bending', to push beyond the boundaries of ordinary urban life - but losing the reality of such environments on the way.

No matter how realistic the graphics become, I argue that due to this glamorised portrayal of the ‘deepest’ and ‘darkest’ corners of the world, the disconnect between ‘us’ and ‘nature’ is not removed in these ‘picture-perfect’ digital Gardens of Eden. Excessive cosmeticization leads to the othering of these environments, placing them out of reach in terms of immersivity, but also physically and temporally, and ultimately away from inspiring a personal connection. The tension between producing the wonder factor (fueled by the pervasive exotic discourse) and the requirement of realism to achieve a plausibility illusion is too strong, and the images become worlds of their own. Heightened by realistic digital displays, this tension leads to a failure to inspire real change in public attitudes towards climate change.

With the risk of being cynical, I would liken the results to a 21st century virtual version of butterfly taxidermy. They quench the desire to look at beautiful things up close, yet your enjoyment of them cannot meaningfully categorise you as a nature-lover, or a climate change activist. I am not alone in this feeling - a review of the 2022 Green Planet AR Experience describes ‘a lovely engaging experience that didn’t shy away from eco-disasters and yet still left us with a feel-good factor for simply engaging with its content’, and Timeout’s review of the Barbican’s immersive Our Time on Earth exhibition calls the displays ‘more of a fantasy than a warning’.

There is nothing wrong with being intrigued and mesmerised by the sights of these exhibits. There is also much to be said about using art to influence public consciousness. I, for one, have already booked my ticket for the upcoming Dear Earth: Art and Hope in a Time of Crisis exhibition at the Southbank Centre, and I am a firm believer in the power of imagery to shape our perception of the world. The only claim I would steer clear of is deeming XR a ground-breaking tool for furthering the uptake of biodiversity conservation efforts. In that respect, I am not quite sure we have found our golden ticket yet.